Coronavirus: India is turning to faster tests to meet targets

India's Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, has pledged to ramp up testing to one million per day over the next few weeks to tackle one of the world's worst outbreaks of the coronavirus.

India's Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, has pledged to ramp up testing to one million per day over the next few weeks to tackle one of the world's worst outbreaks of the coronavirus.

But can he achieve this, and are the tests being used reliable?

How much testing is India doing now?

On 11 August, India carried out more than 631,000 tests, according to data from the international comparison site, Our World in Data.

However, daily figures released by the Indian government are slightly higher than this, with the latest data showing there were 830,391 tests on 12 August.

Prime Minister Modi's ambition is to achieve a million tests each day.

This is a large number - but it should be put in the context of India's population of 1.3 billion.

If you look at tests per 100,000 people, India currently carries out around 45 tests each day. In comparison, South Africa tests 50 people, for Pakistan it's nine tests a day, and for the United Kingdom it's more than 220.

What kind of tests is India using?

While boosting testing is regarded as a key part of the battle against the coronavirus, it's the type of testing which experts say is causing concern.

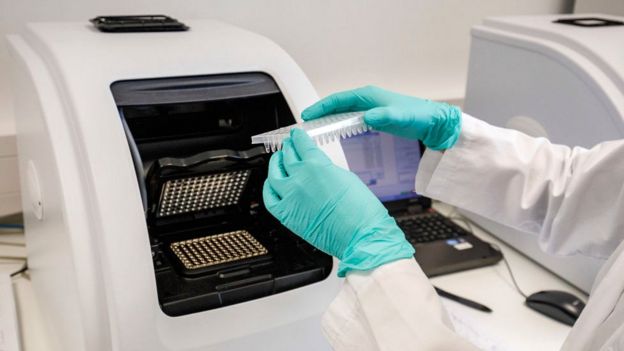

The one that's been most commonly used globally is a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test, which isolates genetic material from a swab sample.

Chemicals are used to remove proteins and fats from the genetic material, and the sample is put through machine analysis.

These are regarded as the gold standard of testing, but they're the most expensive in India and take up to eight hours to process the samples. To produce a result may take up to a day, depending on the time taken to transport samples to labs.

In order to increase its testing capacity, the Indian authorities have been switching over to a cheaper and quicker method called a rapid antigen test, more globally known as diagnostic or rapid tests.

These isolate proteins called antigens that are unique to the virus, and can give a result in 15 to 20 minutes.

But these tests are less reliable, with an accuracy rate in some cases as low as 50%, and were originally meant to be used in virus hotspots and healthcare settings.

It is worth noting that these tests only tell you if you are currently infected and are different from antibody tests that tell you if you were infected in the past.

India's top medical research body, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), has approved the use of three antigen tests developed in South Korea, India and Belgium.

But one of these was independently evaluated by the ICMR and the All Indian Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), which found that their accuracy in giving a true negative result ranged between 50% and 84%.

"The antigen test will miss more than half of truly infected cases," Professor K Srinath Reddy, of the Public Health Foundation of India told the BBC.

This can be for various reasons like the swab sample wasn't good enough, the viral load in the person or even the quality of the testing kit.

The ICMR had issued guidelines saying those with negative results from an antigen test should also get a PCR test if they show symptoms, to rule out a false negative.

Are rapid tests recommended globally?

Rapid or diagnostic tests may or may not use antigens in detecting the virus.

In the UK, the most common type of rapid test has an error margin of 20% for giving false negative results.

But the rapid test kits developed by Oxford Nanopore are said to pick up 98% positive cases, although that needs independent checking by researchers and health experts.

Both these rapid tests use genetic material, not antigens, hence are more reliable.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Food and Drugs administration have also advised getting a PCR test if you test negative in a rapid test.

The United States is vying to develop such diagnostic kits you could buy at a store, swab your nose or saliva and get the results within minutes, like pregnancy test kits.

But the FDA guidelines for approval of such kits say that their performance has to be nearly as good as lab tests.

The US is already using antigen test kits by BD and Quidel which have a sensitivity of 71% and 81% respectively, higher than those used in India.

Are Indian states missing coronavirus cases?

Many Indian states, which decide their own testing protocols, have been increasingly turning to the rapid antigen test.

ICMR announced on 4 August that up to 30% of the total tests conducted in the country were antigen tests.

Delhi was the first state to begin antigen-based testing in June, and many other states followed suit. It began using them on 18 June, although there is no data publicly available until 29 June.

We've looked at data from 29 June to 28 July, which shows Delhi conducted a total of 587,590 tests, of which 63% were antigen tests.

But the available data shows that less than 1% of those who tested negative in an antigen test went on to have a PCR test, and 18% of those who did tested positive.

The recorded infection rate in the capital has fallen in recent weeks, but experts suggest that could be because many cases have been missed.

The authorities have now asked testing centres to conduct more PCR tests.

But data shows that more than 50% of the tests conducted are still antigen tests, despite the Delhi High Court's order that it should be used only in hotspots and healthcare settings.

The southern state of Karnataka started using antigen tests in July, aiming for 35,000 a day across 30 districts. Although they haven't been able to achieve the target, the number of antigen tests has been going up, and the number of PCR tests coming down.

Available data suggests that in the last week of July, 38% of those who initially tested negative but had symptoms and then took a PCR test, came out positive.

In Telangana state, the government also ramped up antigen testing in July.

Although the state does not provide daily data on how many PCR and antigen tests are conducted, there are currently only 31 government and private labs equipped to do PCR tests, as against 320 government facilities for antigen tests.

India's worst affected state, Maharashtra, first began antigen tests in Mumbai. The city's municipal corporation reported that 65% of those who had symptoms of Covid-19 tested negative in the antigen test, but went on to be positive in a PCR test.

Dr Anupam Singh, a public health expert, says there are some advantages to the rapid tests: "It allows a faster detection process and means you can quickly detect highly infectious individuals with a high viral load who might be so-called super-spreaders."

But he also has concerns about this strategy, which can potentially miss many infections.

"As PCR testing requires higher investment and resources, the authorities have switched to a focus on reducing deaths, and catching highly infectious people - the low-hanging fruits," says Dr Singh.

So the switch to rapid antigen testing may satisfy performance targets and meet public demand for more testing.

But it runs a real risk of not revealing the true extent of the outbreak - unless it's backed up by continued PCR testing.

source: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-53609404